Editorials

Below are my thoughts and feelings about artificial intelligence and its impact on our lives today and tomorrow. Subscribe below for more.

Years ago, I found myself on a business trip to California, driving through morning traffic from Los Gatos to San Francisco.

I have traveled this way many times and had my trip planned and figured out, except for the last couple of miles in the city. San Francisco is a complicated place with lots of traffic, people everywhere crossing the road in front of you, and many one-way streets. It’s difficult for an outsider who is used to the simpler lifestyle of Colorado.

Thus, to avoid the inefficiencies, complications, extra stress, and possible loss of time, I launched a navigation program on my cellphone, relaxed, and started following its directions.

My curiosity was quickly awakened when, instead of asking me to take 17 to 85 North, the program sent me on a small road towards Saratoga Ave. While thinking about it, I was enjoying a nearly empty road. Then, before reaching Saratoga Ave, the program asked me to turn again––this time onto an even smaller street. The street was also nearly empty, and after a few miles of relaxed driving, I successfully reached 85.

So far, the trip was a delight.

I enjoyed the ride until I was within a mile or so from 280 North towards San Francisco. At this point, to my surprise, the navigation system asked me to exit on Steven’s Creek Blvd. What? I could already see the sign for 280 North towards SF and decided that this was a navigation mistake. And so, I simply ignored this advice and continued forward on 85 North.

In no more than 30 seconds, I was stuck in a traffic jam while the program was still giving me the instructions on how to exit on Steven’s Creek, travel some short distance, and get back on 280 North. I realized at that point that the program was always correct and was just trying to simplify my life and save me a few minutes by finding the least busy route.

This is all great, I thought, but how does it always know where the good route is? It doesn’t have any “traffic sensors” to rely on, right?

At this point, I had a minor epiphany when I realized that (and I imagine most people are fully aware of this fact by now) I was carrying such a sensor in my hand all the time. Nearly every phone around me was sending information back (to its mother-ship). At any given time, the owner’s location, speed, and direction were measured and reported. On the roads everywhere, millions of sensors embedded into millions of devices kept reporting on their owners.

And a computer somewhere far away was monitoring them constantly, analyzing them, reaching lightning-fast conclusions, and converting them into recommendations—the Internet of Things in action.

The speed of moving sensors has declined simultaneously? And a lot of sensors are clustered together? It is likely a traffic jam.

High sensor velocity? Likely, this road is not congested.

Few sensors reporting back from this particular street? This street is empty, I guess.

But a moment later, I had another epiphany––a bigger one, which then made me concerned.

Until that moment, I always thought of my navigation system as a tool that blindly follows my will and does anything possible to make my trip safer, faster, and more comfortable—a loyal assistant without personality or agenda.

At that moment, however, I realized that this, my assistant, could also be… assisting someone else: constantly manipulating me and the others on the road and off the road––all who blindly follow its directions. The ease at which it was able to send me to streets I didn’t even know existed and away from the path I was planning to follow quickly led me to the following realizations:

· I am not just being informed about the road anymore. It is more than that now.

The navigation computer can make me go anywhere it wants—assuming I am entirely new to the area.

· If it decides so, it could create traffic jams at specific places by sending lots of cars to one location, all at the same time.

· It could make me and others pass by a particular billboard, 7-11 store, or a restaurant and even slow the traffic down there to allow us to study the ad or decide to stop by for a bite.

· It could paralyze the traffic to benefit a selected person or give an advantage on the road to some preferred clients.

· It can cause me to be late for my flight or train or business meeting.

· It can keep some areas of the city ecologically cleaner by re-directing traffic around those areas.

· It can do a lot of other things. And it all depends on who writes its algorithm.

In other words, I have realized how much power this “simple” IoT tool has over all of us–– and that is just for the people on the road.

Then, I almost felt an all-seeing eye of the machine in the sky watching my every move and constantly adding new data to a nearly limitless data repository––all to be compared, analyzed, and classified to ultimately predict every move I make and every step I take. And to change my actions (and my life) if it is of benefit to that machine.

Then, I decided to turn my navigation system and the location services off and go “off the grid,” but SF is a difficult place for an outsider to navigate. I was in a bit of a hurry, and––after some internal battle between the rebel and the pragmatist–– the latter decided to keep the system “on” for just a little bit longer.

“But I will turn it off tomorrow!” I told myself.

That was many years ago. I am still using it every single day.

In the Carrying Hands of the Machine

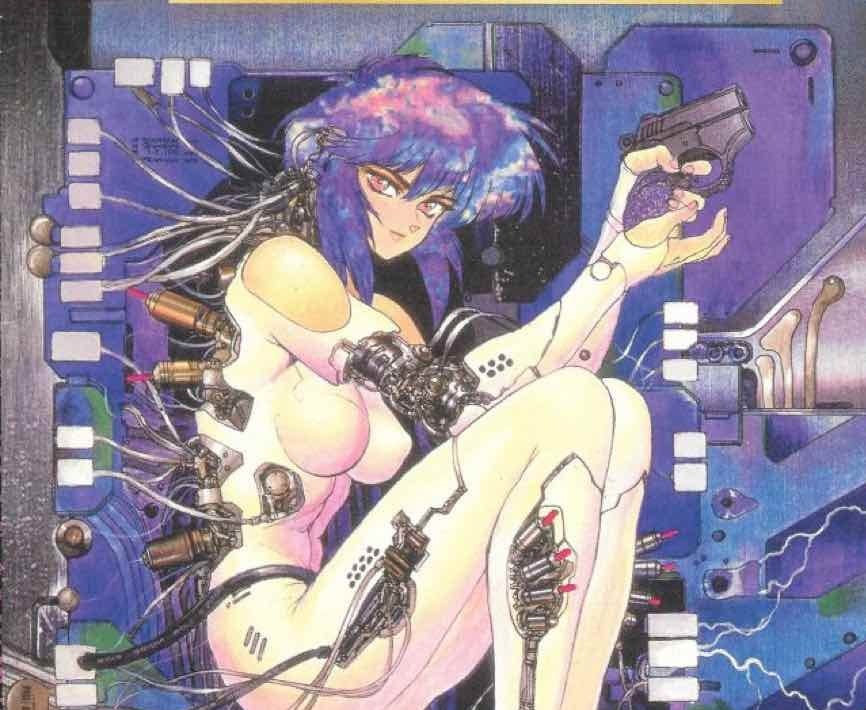

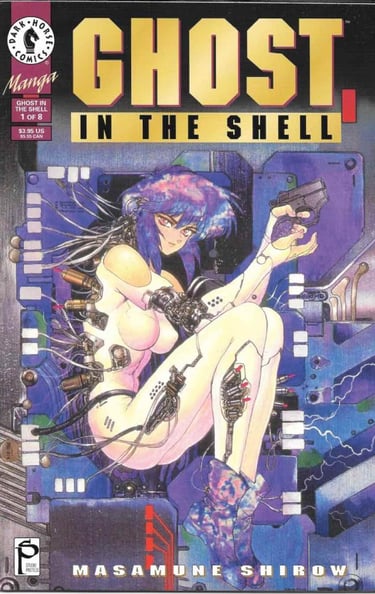

Anyone familiar with Shirow Masamune’s manga series and its animated adaptations called Ghost in the Shell will understand my excitement when the movie with the same title was finally released in 2017. But, of course, anyone familiar with how Hollywood changes good stories and books and remakes older movies to make them suit their current needs and agendas should always be worried. But I was cautiously optimistic because of Scarlet Johansson, who was staring in the role of Major Motoko Kusanagi.

For those not familiar with Ghost in the Shell, all you need to know is this:

· The action takes place in post-WW3 Japan in approximately 2030.

· By then, AI and cybernetic implants were so developed and pervasive that a large majority of the population is partially or fully cyberized. Cyberization varies from simple elements like human vision improvement to a full-body replacement.

· This world is the IoT world, connected to machines and humans, with everything and everyone being somewhat interconnected.

· Most, if not all, of the population can link to the Web and each other using small interface connectors located at the back of their necks.

· New technology has dramatically changed our future world and improved it in many ways, creating, however, new cyber-brain-related issues and illnesses, new sources of social tension, new types of terrorism, and even new brain-hacking crimes.

Major Kusanagi is a leader of an elite unit focusing on cyber-crime and cyber-criminals. All team members have unique skills, such as hacking, data mining, cryptology, and solid military training. These skills and training allow them to fight and, most often, win.

The Shell for Your Ghost

Why do I know this? When the first comic book (1995 in English) and the animated film (1995) were released, I was much younger and even more interested in science fiction and the future of technology than I am now. Plus, I was living and working in Japan at that time.

What fascinated me about this story is how complete and developed Shirow Masamune’s world was and how it was filled with millions of large and small details, which made it so realistic. A near-perfect example of what the writers call ‘world-building.’

This story, which includes multiple comic book series, several animated series, and several animated films, is, in my opinion, the complete vision of the future, in which Artificial Intelligence and human-machine interface become a common thing. However, humans still manage to preserve their humanity and make technology a part of them. And, when their humanity is threatened, they fight for it.

And this is something we will be facing one day when we gradually ‘improve’ ourselves with better parts.

Where does the machine begin and the human being end?

With a new artificial hip? Definitely not.

Tooth implant? No.

Artificial limb? Nope.

Bionic eye? Neha...

Heart implant? Unlikely.

Brain implant to help with seizures? Unlikely.

All of the above at the same time? Still a resounding no.

We just don’t know yet how to do more of this. What about memory enhancement devices? Some sort of electrodes implanted in specific areas of the brain to bring back particular memories? Or changing some of these memories? How about something to speed up our thought process, enhance our cognition? Make us do the math in our heads? All of the above at the same time? We are getting closer now…

One day, we will reach the point when we have to rethink the definition of being a human. This might be a frightening experience for many, with many debates, suggestions, ideas, and anger—with new social movements rejecting those ‘heavily augmented’ or, au contraire, fighting for their rights. Maybe at that time, somebody would decide to look back in time, at the Ghost in the Shell series… which already offers many answers to the above questions.

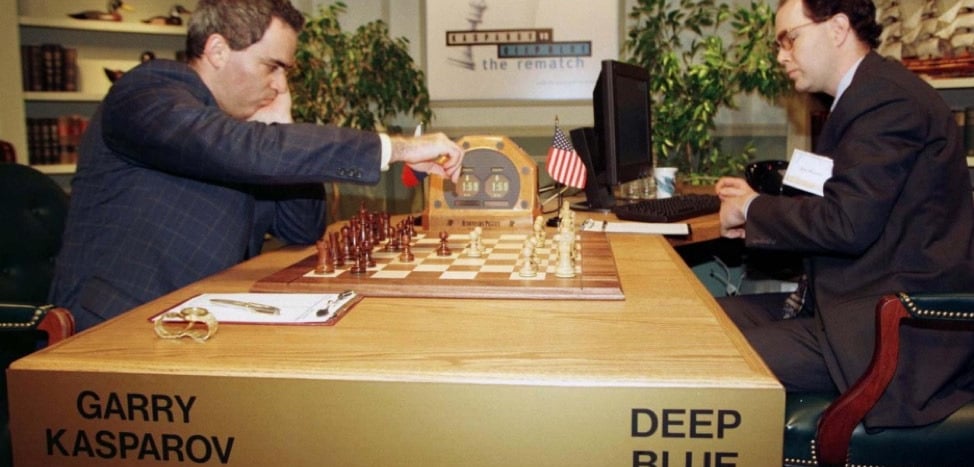

Chess is a fascinating game that hasn’t lost its appeal even after the strongest human player of the time was finally defeated by a computer. I refer to the historical 1997 face-off between Garry Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue. In New York City, Deep Blue won by just a slight amount, 31⁄2–21⁄2. However, this small victory has taught us a lot about chess, computers, and ourselves.

We’ve learned that machines can consistently outperform humans in those competitions (games, conflict, planning activities, etc.) where all the rules are well-defined. Moreover, no matter how complex these rules are, given enough time, machines’ superior computational abilities and nearly unlimited memory (storage, really) win against human creativity, intuition, and reasoning.

Since that victory in 1997, chess machines (or chess algorithms) have become stronger with every passing year. Nowadays, even the most brilliant player of our time, Magnus Carlsen, doesn’t have a chance against Stockfish or, even worse, AlfaZero, even if the world’s top ten strongest grandmasters aid him.

Further, we also learned that this demonstration of a computer’s ability to imitate intellect in one field doesn’t mean it is getting closer to human-like intelligence. For example, while Deep Blue and all the modern chess programs are brilliant at the one thing they are created for, winning chess games, they are pretty useless for everything else. And to become helpful in any new areas, they have to be almost wholly modified.

This remains a confusing point for those who follow the field of AI by reading articles in popular magazines. These articles create the impression that with every step towards better image or speech recognition, successful Jeopardy performances, or successes in chess or Go, computers and algorithms truly acquire human cognitive abilities.

Modern chess algorithms effectively demonstrate that this is not the case. While being 1,000x (or even 1,000,000x) better than humans in chess and ‘thinking’ 50 or more moves forward during each game, these algorithms are less capable of solving most practical tasks than babies.

Finally, we discovered that despite being unable to compete with computers, we still find the ancient chess game fascinating, want to play it, and want to succeed at it. Cars are faster than humans, but we still compete in running. Machines are stronger than us, but we still compete in weightlifting. Chess is no different––we will continue to play and compete.

Some time ago, I finally reached the Lichess.com rating of 2,000. It took me 4.5 years and 11,818 (!) games to do it. I have spent 45 days, 9 hours, and 38 minutes playing non-stop to get to this point. And I only played when I had time for it.

I wish I had the luxury of playing chess online with anyone worldwide when I was just ten years old. But, alas, it wasn’t possible then. To play chess, we needed a chessboard, a clock, and a willing partner, who was often difficult to find. Some people even played by mail!

The result was that it was hard to play more than a few hundred games per year. Today, with the help of Lichess.com (or Chess.com or a similar platform), I can play on the order of 2,500 games per year without ever leaving my house.

Often, those who complain about the damage and dangers of technology overlook simple examples like these. These are instances when technology changes our lives beyond recognition and makes it better and more enjoyable.

Playing Chess In the Age of AlfaZero

One major issue with computer-generated films having human characters is commonly referred to as the Uncanny Valley.

The term “uncanny valley” relates to an uncomfortable feeling we have when seeing or interacting with a computer-generated character or a humanoid robot that is nearly identical to us and appears almost but not exactly like us. In the end, this causes some sort of brain confusion, and ultimately, a feeling of fear or even repulsion. If the robot or CGI (computer-generated imagery) character looks very different, then things are OK. If not––expect that confusion, anxiety, fear, and repulsion.

Therefore, “crossing” the uncanny valley is generally considered to be a crucial last step before CGI movies and CGI characters can become... well, like us. And be accepted by us.

I am slowly realizing now that there might be another path. Maybe we don’t need the CGI characters to look exactly like us! Maybe, they can look similar to us but be even more interesting, attractive, and beautiful? And perhaps the actual actors who we are used to watching on screen can be replaced, and we will be OK with it?

This 6-minute computer-generated clip is an illustration of what I mean; almost every character in this clip looks, in my (slightly biased) opinion, as attractive and as enjoyable as any actor I have seen in the past. In addition, the whole animated film is simply gorgeous.

Here is what I am asking now: how many years will it take for most movies to switch to CGI characters entirely and for the human actors to become a rarity?

I am guessing 10-15 years, no more. But, what do I know… to err is human.

CGI Is the Future

The question sounds intentionally provocative, but it is only so if you think this question pertains to the current world. But if you think about life in the future, say, 100 years from now, this question becomes as natural as the concept of singularity, machine intelligence exceeding that of a human, or transhumanism and humans (and human society) merging with machines.

All of this might look like fiction for now, but not as something entirely impossible or contradictory to the fundamental laws of nature, science, and technology. So, let’s imagine that we eventually manage to create an AI that is general enough to address questions of our society, economics, ecology, and culture and can interface with us in a human-like way––speak, listen, write, read. Imagine an artificial intelligence that matches ours in every possible way and exceeds our computational and analytical powers. Imagine that this is possible.

Now, think of the significant number of problems humans always have with the various ideas of governance experienced thus far:

Authoritarianism (including absolute monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy, and dictatorship) can work for some time but depends too much on the personal characteristics of a leader. Eventually, power corrupts the individual, leading to significant abuses, nepotism, neglect of the existing laws, the disappearance of fundamental freedoms, the police state, societal poverty, and general suffering of the population.

Democracy, as Churchill said, “is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” Unfortunately, this doesn’t sound like a compliment. Democracy can be very inefficient at times and is often undermined by the corruption of government and elected officials, lobbyism, one-sided and biased mass-media, excessive bureaucracy, political nepotism (yes, even for democracy), and could “deform” over time into Potemkin’s Villages with great-looking facades but rotten guts.

Some people desire “anarchy” as a form of governance (where the centralized government is unnecessary). Still, to my knowledge, this approach has never led to anything successful at any significant scale.

What is wrong with the above forms of governance, and why are even the best of them still “the worst”? Sorry to say it, but the weakest link is always us.

The people.

None of the above (or any other) governance systems fit, satisfy, work for, or please one hundred percent of the population.

There are always people who just don’t want to accept all the existing system’s social, economic, and other rules (and responsibilities). And some others find ways to abuse those rules. These “bad apples” use the system for their benefits, exploiting its weaknesses and generally taking advantage of it, often eroding or destroying the system itself. A couple of “bad apples” could, over time, damage even the best system. Unfortunately, lots of bad apples can turn all the apples “bad.”

What most people ask from their elected or self-elected leaders is to be honest, selfless, just, faithful to their promises, and for them to generally take care of us, others around us, and the country. And the world.

Instead, those who govern often take advantage of us, abuse their powers, break laws, get rich and make their families and friends rich, and once elected, try to maintain that power for as long as possible. Sometimes they even trade the entire country for their benefit and care even less about the rest of the world.

Now, let’s ask the same question again: wouldn’t it be better to outsource the above “governance” functions to some entity that cannot be corrupted, isn’t interested in money or fame, doesn’t have family, children, or friends to make rich, doesn’t have mood swings, doesn’t hold grudges, doesn’t get emotional, angry, or upset, and doesn’t care if it controls the whole world or just one tiny city? An entity that operates by clear objectives we set and tries to reach these objectives in the most efficient, inexpensive, and fast way?

My answer to this question is, “Yes!”

Many people will probably want to agree as well. And many others will first ask questions such as the following:

· How could we invent this new form of governance—the AI Government? Is it even possible?

· Why should I trust a machine more than a fellow human politician?

· How do we know it will work better than a human?

· Who will create this AI for governance, and how do we know they wouldn’t program something malicious into it?

· What if this AI decides to take control of all of us? We will become slaves! (Hello, Matrix!)

· What if it starts a world war and kills us all? (Hello, Skynet!)

· Finally, how do we replace/refresh this AI government from time to time? Is the process going to stay democratic?

These are all excellent questions.

Let me try to address them indirectly by comparing a human chess player to a modern chess computer “engine.”

To be continued...

Do We Need AI Government?

I have often seen it while watching the chess commentators (typically, Grandmasters of the highest grade) performing the game analysis in real-time.

These GMs will consider different options for both sides and, infrequently, when the situation becomes too complex and unclear, say something like this:

“Hey, let’s check with the chess engine now... Oh, it gives an advantage to the Whites, but I don’t see why... It says to do... WHAT?! And then... WHAT?! No... these are not human moves; the players will not do that. This is too deep and too machine-like….”

The truth is that even the strongest Grandmaster looks like a child when being compared with the machine.

But this is precisely why this GM is using the help of that machine!

Lucky for the game of chess, nobody suspects that “Stockfish” or “AlfaZero” have ulterior motives, biases, don’t like a particular player, or want to take advantage of somebody. On the contrary, chess engines are considered fast, powerful, and accurate, and objective analysis and decision-making tools capable of finding the best solution for any situation and being helpful to us by simply being better than us.

Tools. And nothing else.

This is precisely what the future AI governments should be:

A fast, intelligent, precise, objectively analytic, decision-making TOOL to find the best solution for any situation and be helpful to us by simply being better than us when it comes to governance. And nothing else.

Machine learning (ML) we use today might already offer a theoretical approach to building and testing such an “AI governance engine” toward creating an entire democratic election process using ML’s training and testing approach that would look something like this:

· Provide the “governance engine” with a training dataset of historical or other examples that are of high value to us and explain how to classify them (for example, “bad” or “good”). Cover many important social, economic, judicial, cultural, and educational fields. For example, imagine thousands upon thousands of statements or questions along with their classifiers/answers presented like this: “Rosa Parks rejected bus driver James F. Blake’s order to relinquish her seat in the “colored section” to a white passenger. Was she right, or should she have stayed in the colored section?” The answer: Rosa Parks was right. The driver was wrong.

Or “greater investments in children’s education” are good. Cutting these investments is bad. Or cutting forest in Amazon delta is terrible. But, on the other hand, reducing industrial water and air pollution is good. We have tons of examples like this from our past and present.

· Keep another dataset of examples with answers for testing. We will use it later to verify that the engine works well.

While this sounds like a good idea, this is hardly practical. So, we should rather wait for the time when the AI can find the above examples in our literature, textbooks, government, and court documents. And learn from them, figure out what is good and what is wrong.

Let’s suppose this is done (even if we are very far from that, this is conceivable). Now, we need to test that AI to make sure it learned the right things.

The general population should take part in creating the list of questions for this test. Millions of people can contribute to it––our AI engine can perfectly answer millions of questions. And this will allow the people to find out what their future governor thinks about those specific issues that are close to the people’s hearts.

Then, there will be the time for an election, where many AI candidates could participate. They might be all trained similarly, but they are not necessarily going to learn in the same way. Some engines will do better in some cases, and others will excel in others. For example, Engine A might score higher on social issues while Engine B will do better in economics. This resembles the difference between the human candidates with different backgrounds and opinions during the elections, which could be used to make the final decision.

Decision on which AI model to use (if any, since they all could also be sent back for re-training) at the end can be made via the same democratic election process we currently have, with people voting. Minus the negative TV ads, mutual insults, and paying the press to dig up dirt on other candidates.

To be honest, if society wants to preserve that last part of the process for “entertainment purposes,” it could be easily simulated by these AI engines as well: there could be plenty of “dirt” found from the “past test results” or the focus of the smearing campaign could be shifted onto the model’s creators––the living people. The actual weak link.

In the end, the decision of when to bring the engine online and when to consider other alternatives again (aka “general AI elections”) should be made by humans. And, humans should have a veto right over the most controversial decisions that the AI government will make.

The gains from such a revolutionary change, which should start at a smaller scale and be tested over time, are difficult to estimate. But, to our shock and great surprise, we might find that nearly ANY social model, form of governance, or economic system will start working well after the people are removed from the daily decision-making process; all their biases, emotions, and personal interests are gone, and the law is consistently enforced without prejudice or corruption.

Over time, different political and economic systems might start converging into one system, the Optimum, which favors the best and most balanced decisions for all the people.

We will all be surprised. We will all be suspicious. We will complain a lot.

We will talk about the long-term adverse effects of this change, about the dangers of losing control, about AI dictatorship, and the end of humanity.

But time will pass, and we will realize that an AI Government is just another tool for us to use, something similar to a city traffic control or a sophisticated thermostat in the house, which is always “on,” is programmable, predictable, efficient—serving us 24×7.

Then, we will concede that new world is a better place to be in. We will get used to it and start enjoying it. Our world will become safer, more predictable, and much better governed.

And, as today with the game of chess, we will accept that there is a superior computing and reasoning Government that we created to simply make lives better.

The tool for all of us.

Do We Need AI Government? – Part 2

Welcome to the Adventure!

If you like action-packed cyber-fiction, subscribe below and stay informed about new books!